Badami in Karnataka, the paradise for history buffs and geological explorers, is a place where ancient temples and rich heritage come together to create a mesmerizing experience. A place where monuments still stand as a memorial to the glorious past of the Deccan Plateau. A place that was once the capital of the mighty Badami Chalukyas in the 6th century CE. The enormous cave temples and the Bhoothanatha temple are still part of architectural history studies.

My emotional connection with Badami began in 2017 when I proposed an archaeological visitor center for my architectural thesis. But this blog is not about Badami’s monuments. This is about the scattered vernacular settlements that evolved around the town. I will write a separate blog about the monuments of Badami later.

“The soul of India lives in its villages.” – Mahatma Gandhi

the geography

Badami is situated at the core of the Deccan Plateau. The geology of the northern Deccan Plateau is unique, with undulating sandstone hills. Within these undulations lie small lowlands where water availability is better. Though the Deccan Plateau is dry and sunny, some non-perennial rivers flow through it, allowing human settlements to emerge. The fertility of the soil made it ideal for cultivating cereals and pulses.

Around Badami, we can see the branches of these non-perennial rivers, which made agriculture possible. Surrounding these vast agricultural lands, we find multiple human settlements that have remained mostly untouched by the growth of modern society. We explored three villages around Badami as part of an academic study: Kendur, Chikkamuchalagudda, and Kuttakanakeri. Each village had its own unique demography.

The street patterns of each village were distinct, shaped by the geography itself. The highlands inside the plains were strategically chosen as the settlement’s starting point. These highlands became the center, with a temple placed at the heart of the village. From here, the streets radiated outward, leading toward the agricultural zones. At the end of each street, small shrines and temples could still be seen. Through interviews and oral history research, we learned that each local deity was once believed to protect agricultural fields from harsh climatic conditions. These trees and shrines represented the spiritual beliefs that helped the villagers survive.

There was also a caste-based hierarchy within the street patterns, but in today’s era, this is no longer very relevant. However, what fascinated me the most was how dynamic the streets were.

the street dynamics

The streets were narrow, mostly between 2.5 to 3 meters wide. The verandahs opening to the streets had more activity than the actual living rooms inside the houses. For this community, the street is the living area. Parents rarely worried about their children because the community itself raised them. The unity of this village community is something every society should learn from. If someone had a problem, the villagers would gather at the Kaliyamman Temple, the highest point in the settlement, where the village head would discuss and conclude a solution.

The streets were filled with life—children playing, women chatting, men playing cards, and cows casually walking in and out of homes. Unlike modern planned settlements, these villages had organically evolved. The row houses were not aligned in a straight line but followed a rhythmic pattern shaped by time and necessity.

architectural of rural badami

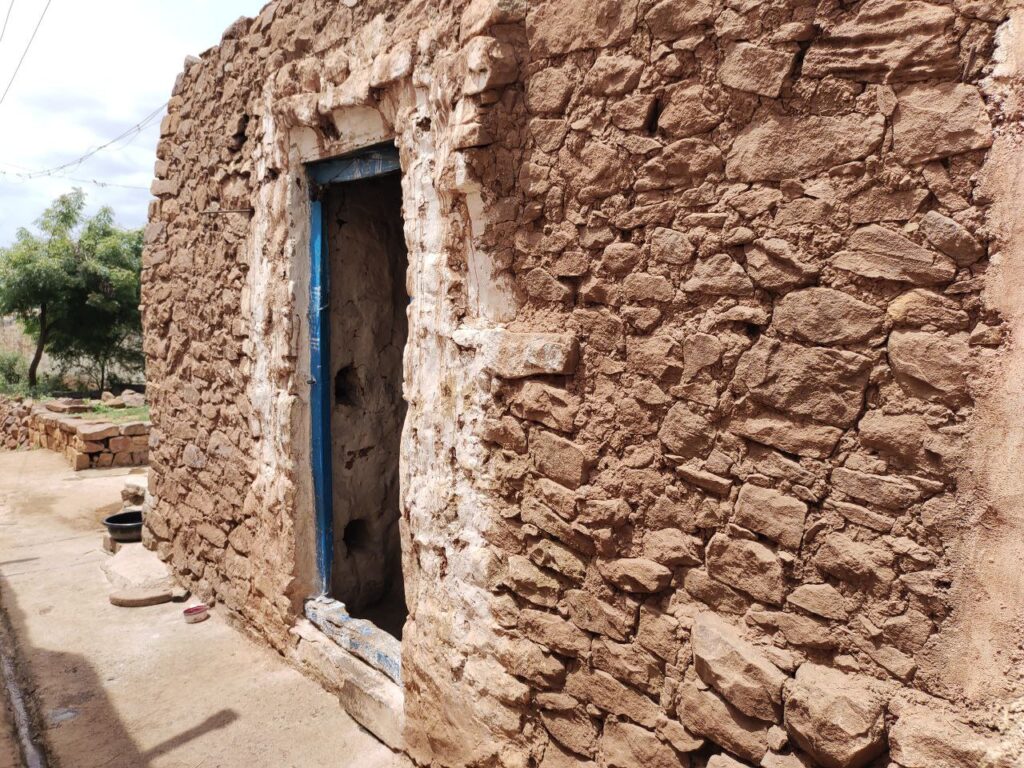

The architecture of these vernacular settlements was deeply rooted in function. There was no separation between human and animal spaces; both coexisted under one roof. A cow inside a home was seen as a divine presence, reflecting the humility of the community. The houses evolved purely from functional needs, with only minimal decorative elements, mostly at the entrance and balconies.

One architectural feature that intrigued me was the sudden shift in ornamentation. The walls were made of locally available stone, plastered with lime or mud, giving them a raw appearance. But the doorways and inner courtyard arches had intricate carvings. The residences were 100 to 150 years old, and when I asked the villagers about the carvings, they simply said, “We had skilled carpenters in our village who did these.” The carvings were fascinating, featuring local flora, fauna, and divine figures.

In terms of spatial planning, the first zone of the house was dedicated to cattle. A mezzanine level above this space stored wooden logs and agricultural tools. The next zone was for the women, just a raised platform from the cattle area, followed by the kitchen, which had an innovative ventilation system. Pots were placed on the roof to allow daylight in, and during rainy days, they were covered manually.

The roofing system was unique, with a thick 50 cm layer of thatch and mud protecting the interiors from the harsh sun. Wooden logs formed the base, topped with a layer of dry leaves, preventing mud and small stones from falling inside. The entire mix was tightly packed and finished with a final mud layer. The stairs were also interesting. Unlike modern stairs with standard risers, these houses had 40 to 50 cm high steps, making it easier for people to climb to the terrace. The street dynamics didn’t just stop at ground level; it extended to the rooftops, where people dried crops and clothes.

While exploring the village, the locals warned me, “Don’t walk on dry areas of the roof; it might collapse!” This made me realize how deeply interwoven architecture and community life were in these settlements.

a living heritage

The villages around Badami are not just settlements. They are living museums of a forgotten way of life. A society where streets are extensions of homes, a place where architecture is not about aesthetics but about survival and adaptation, a settlement where cows, people, gods, and homes coexist in harmony.

These experiences made me wonder how much of this will survive in the coming decades. With modernization creeping in, will these unique organic villages retain their identity, or will they slowly fade into uniform concrete grids? I left Badami with more questions than answers.

I still remember a young man named Anand, who helped me a lot during my visit. He was an engineering graduate from Bagalkot, and I was truly inspired to see someone from a small village pursuing his ambitions beyond his hometown. Even now, we stay in touch—he often reaches out to me for suggestions and opinions. It makes me happy to see him thriving in Bangalore, chasing his dreams with determination.

Those who wish to read about the history of Badami, go through the link below https://www.telegraphindia.com/my-kolkata/places/badami-the-famous-rock-cut-cave-temples-of-karnataka-are-a-piece-of-glorious-history/cid/2020232

Want to explore similar rural settlements of Indo-Tibetan border? Go through the link below, https://heritagevedanta.com/niti-village-a-remote-himalayan-paradise-on-the-indo-tibetan-border/

This blog is based on my travel done during the settlement study for semester 5 from the College of Architecture,Trivandrum, in 2023.

Discover more from HERITAGE VEDANTA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.